In the midst of California’s Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, the Farallon Islands are also sanctuary for the largest bird population in the lower 48 states and central to immense populations of protected marine animals that feed there on its food-rich waters. Humans feed there, too, because many fishermen derive their—and our—livelihood there.

The Farallon Islands are a Native American sacred place, their islands of the dead. The California Coastal Commission ignored that argument in making their decision to allow the coming poison drop there. There is no evidence that they or the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service consulted with any or all of the tribes that would be affected by a poisoned environment.

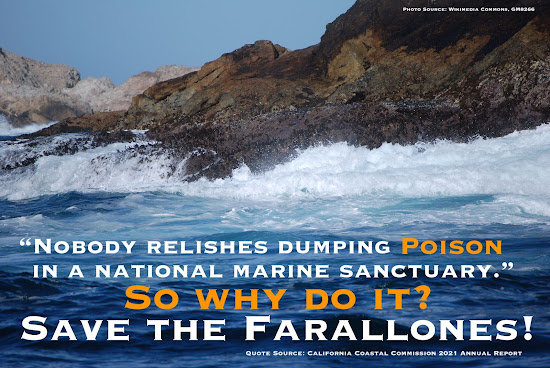

The islands and their waters are currently threatened with helicopter drops of 1.5 tons of Brodifacoum-laced pellets, a rodent poison banned in the rest of California, to kill a population of mice there (http://poisonfreesanctuary.org).

The drop is promoted by the islands’ manager, Point Blue, supported by Island Conservation—both California coastal environmental organizations—and approved by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and the California Coastal Commission.

The poison will be dropped in the next year, two years on the outside, and will spread into the avian sanctuary and the ocean, with multiple animals, perhaps whole species, dying. Raptors who migrate there seasonally to feed will also be poisoned.

The poisoned will bleed to death, and their scavengers can and will, too. The bykill of the poison drop will be substantial and an epic hazardous materials disaster. There have been numerous other island poison drops with massive failures and bykills to date.

The Farallon Islands are regularly treated by the application of herbicides, including glyphosate, and have been for years.

These islands are considered to be sacred to California Indian tribes as their Islands of the Dead, part of coastal mortuary complexes with Point Reyes for the Coast Miwok and with the West Berkeley Shellmound for the Ohlone (http://www.sacredamerica.org/2018/04/dancing-on-edge-of-pacific.html; http://www.sacredamerica.org/2021/11/spirit-paths-and-sacred-places-point.html). The West Berkeley Shellmound and Point Reyes have recently sustained other threats as well.

Very soon, the Farallons will be islands of the dead. Again. Poisoned to death.

The wider environmental community and sanctuary statuses were other, bigger antidotes against the poison. However, local environmentalists have been compromised by major funding and misinformation. The marine sanctuaries along the coast will be next to be compromised.

Archaeological evidence of human habitation from these Pacific Coast sites and the Continental Shelf would increase the perception of traditional cultural heritage value of these places and could furnish more evidence and arguments against the poison drop. No one who is for the poison drop or more fossil-fuel extraction would want that to happen.

Submerged Indian traditional cultural places are deemed possible on the Continental Shelf, from before and during ocean-rise flooding, roughly from 18,000 years ago to 6,000 years ago, and would be “extremely significant” if discovered (https://farallones.noaa.gov/heritage/firstpeoples.html).

Human habitation on the Continental Shelf in California is not only possible, but predictable. A site in southern California has been dated to 200,000 years ago, Santa Rosa Island has been dated to 37,000 years ago, and there are habitation sites in Mexico dated to be over 280,000 years old (https://tipdba.com/database/).

There is a resistance in mainstream archaeology to admitting these dates are possible, as well as resistance to admitting this in the Department of the Interior (DOI) and in the energy industries.

The DOI’s National Park Service (NPS) published a series of papers in the 1980s and later on submerged archaeology sites off Point Reyes and the Farallons, primarily shipwrecks. They found stream channels worn into the bedrock under Drake’s Bay—a clue to human habitation, wrote wistfully about the possibility of finding human habitation sites, but apparently didn’t look much further (https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/maritime/pore.pdf).

In 2013, the DOI Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) published a report,”Inventory and Analysis of Coastal and Submerged Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Pacific Outer Continental Shelf” (https://espis.boem.gov/final%20reports/5357.pdf). Authors were ICF International, Southeastern Archaeological Research, both publicly traded corporations, and Davis Geoarchaeological Research: “The goal of this study is to assist BOEM in the identification and location of underwater and coastal cultural resources along the Pacific coast to enable them to consider what effects the installation of energy facilities on the [Pacific Outer Continental Shelf] may have on these resources (231).”

An unstated goal of this study was to diminish and dismiss Native Americans’ claims for underwater and coastal resources along the Pacific Coast.

This paper asserted, among other claims: there might be prehistoric underwater archaeology sites off the coast, more likely on the southern coast (67); there wouldn't be anything before 14,000 years ago because that was the earliest probable date (83); inhabitants were not likely to be PaleoIndians but Paleoarchaic [i.e., not Indian] because they didn’t leave behind enough of the “true PaleoIndian” arrowheads (37); there were only a few kinds of traditional cultural properties where an "uninhibited view of the ocean” (175-177) mattered, i.e., without drilling rigs; and Coast Miwoks weren’t around until 4,000 years ago anyway (89).

Like the poisoned birds on the Farallons, these arguments won’t fly. They are fraudulent claims, manufactured to suit the interests of the energy companies and eliminate Native American claims. The authors, BOEM, and DOI were rubber stamping energy development along the coast.

- Their coastal analysis of likely human habitation sites does not hold water in terms of predictive accuracy, especially when predictability was admitted to be equivocal: “the site location predictive model suggests that the value (and the assumed potential for holding a site) of any given grid square increases proportional to latitude, in a southerly direction . . . Conversely, this fact can also be taken to suggest that sites are more likely to be concentrated in greater frequency within the highest predictive value alluvial buffers of modeled stream systems toward the northern end of the POCS study area” (67).

- Fourteen thousand years ago is not the limit of human habitation on the coast when other sites in California are dated from 37,000 years ago upwards to 200,000 years ago. (https://tipdba.com/database/)

- PaleoIndian vs. PaleoArchaic was an attempt to prove that Indian aboriginal and legal claims to America don’t really matter, after remains of the Kennewick Man, found in 1996 and dated to 8,340–9,200 years ago, was promoted by some scientists to be Caucasian and here first. The Kennewick Man was later identified by DNA to be Native American and returned to his related tribe around 2015 (https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14625).

- The lack of an expected artifact—especially when the lack is self serving—does not prove the absence or presence of a people.

- An “uninhibited view” of the ocean or lack thereof is inappropriate in this context and certainly not the arbiter of what is sacred to Native American peoples.

- Neither are the authors’ subjective, self-serving, and non-Native judgments about the character and relative importance of their arbitrary categories of what matters.

- The 4,000-years-ago arrival of the Coast Miwok is an unproven and antiquated hypothesis (https://tipdba.com/database/).

- “The majority of Native Americans [in California] receiving an outreach letter did not respond” to researchers’ requests for information about sites (162), that is, two tribes furnished information out of 124 contacted, making for completely inadequate tribal input.

One of the major energy developers along the Pacific Coast is Chevron. Since Chevron's main offices are located in San Ramon, California, their sphere of influence is larger in California, even though other fossil-fuel companies are involved in similar efforts.

The Packards of Hewlett Packard and the Packard Foundation, heavy environmental funders on the coast and elsewhere, have a direct "pipeline" to Chevron. David Packard served on the board of directors of Chevron Corp. from 1972 to 1985 (https://biography.yourdictionary.com/david-packard). He even had an oil tanker named for him—the David Packard, built in 1977, was operated for Chevon (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Packard). So it is very likely that Packard wealth is at least partially due to, influenced by, and perhaps still invested in Chevron. Its current directors are major owners of stock, so this may have been true for David Packard as well.

Before he served on Chevron’s board, David Packard also served as Deputy Secretary of Defense from 1969 to 1971, in the Nixon administration. He managed the Pentagon. “Deputy Secretary Packard procured an unwritten agreement from Secretary Laird that he could manage the Pentagon” (https://history.defense.gov/DOD-History/Deputy-Secretaries-of-Defense/Article-View/Article/585238/david-packard/). Packard resigned in 1971 to return to Hewlett-Packard and to join Chevron leadership.

Packard Foundation money has heavily funded Point Blue's operations, and Point Blue's management at the Farallon Islands is now questionable. It has control over underwater research and access there and surrounding areas, so much so that finding archaeological evidence of Native American habitation there would be discouraged, the evidence potentially destroyed.

Starting in 2020, Chevron has been decommissioning five of its drilling rigs on the Continental Shelf. It is an empty, public-relations gesture, as it has abandoned very many others (https://www.chevron.com/stories/west-coast-decommissioning-program). Chevron has 16,000 drilling rigs in operation in the State of California. There is apparently the possibility of conversion of some rigs to wind and wave energies, so Chevron may be biding its time until the initiation of Blue Carbon offset projects (see below) may make clean up and conversions not only possible, but profitable.

Chevron has recently failed in Australia by delivering only half of promised carbon sequestration over a five-year period (https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jul/20/a-shocking-failure-chevron-criticised-for-missing-carbon-capture-target-at-wa-gas-project). The company has also failed to clean up its drilling sites in Australia (https://www.boilingcold.com.au/wa-onshore-and-coastal-oil-gas-clean-up-to-cost-billions/).

Big fossil fuels and their money have now polluted the California State government and Washington, D.C. and are poised for more poisons. The poison drop may become a wedge in opening up the marine sanctuaries to more profit from drilling, mining, and other resource extraction, including sand dredging.

Chevron has a reputation for its underhanded tactics, aggression, and dishonest dealings. Their public relations firm in California, Singer and Associates, is efficient in polishing the Chevron brand. Indigenous opposition worldwide, in particular, has pushed back and cost Chevron, and the company is now retaliating. Attorney Stephen Donziger was subject to private prosecution by Chevron’s law firm, Gibson Dunn, for Donziger's role in a $9.5 billion dollar court award to Indigenous peoples in Ecuador against Chevron for massive pollution (https://amazonwatch.org/news/2020/0615-chevron-is-a-champion-of-environmental-racism; https://www.thenation.com/article/environment/donziger-house-arrest-prison/). Gibson Dunn attorneys also filed a pro bono Indian Child Welfare Act case against a Navajo family in September 2021 (https://lakotalaw.org/news/2021-09-17/icwa-sovereignty).

It is apparent that the law firm is deliberately punishing and threatening environmental activists, Indigenous people, their children, and their sovereignty.

Native American Debra Ann Haaland, Laguna Pueblo, was appointed Secretary of the Department of the Interior this year, the same DOI whose BOEM commissioned the 2013 report to diminish Native American interests in coastal and offshore California. DOI also is home to USFWS, who approved the poison drop, and to NPS, manager of Point Reyes, which has been in the news recently about abusive management of elk herds and extended private ranching leases on public lands. Public relations needs were no doubt served by Haaland’s appointment.

The California Air Resources Board’s (CARB) mine methane capture carbon offset protocols were developed in 2014 with fossil-fuel industry input and tailored to industry demands. Subsequent offset projects were furnished by the fossil-fuel industry (http://www.ienearth.org/docs/California-Methane-Offsets-Briefing-%20IEN.pdf).

The suspicion now is that the fossil-fuel industries, particularly Chevron, are hoping that the Farallon Poison Drop is another disaster to profit from, more crisis capitalism.

Already able to profit that way, Chevron owns real estate statewide in California, in particular defunct oil fields, plus a housing subsidiary, Pacific Coast Homes, that has morphed the polluted fields into housing developments. The City of Fullerton recently purchased a parcel of oil-field land from Chevron and Pacific Coast Homes with more than ample state and federal funding: “The City has received $27.45 million in grant funds from agencies such as the California Wildlife Conservation Board, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the State Coastal Conservancy. This is above the appraised price of the east side of West Coyote Hills of $18.040 million” (https://fullertonobserver.com/2021/11/23/city-to-own-nearly-half-of-coyote-hills-as-open-space/; https://www.coyotehills.org/about-west-coyote-hills/).

It’s obvious that big fossil-fuel companies in California want more, including offshore drilling and mining. Offshore drilling has proliferated in California (https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2022/1/11/2073926/-Critics-Say-Newsom-s-Proposed-2022-23-Budget-Falls-Short-on-Confronting-Fossil-Fuels). Chevron is also interested in sponsoring California carbon-offset projects.

The State of California is currently proposing the restoration of California's coastal and marine ecosystems to increase carbon sequestration under CARB’s new Blue Carbon offset protocol for their Cap-and-Trade program (https://resources.ca.gov/Initiatives/Expanding-Nature-Based-Solutions?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery).

There are still multiple issues about the effectiveness of Cap-and-Trade. Carbon offset projects have major, systemic problems that can’t effectively be fixed (https://no-redd.com/trading-on-thin-air-fictive-redd-carbon-chaos-in-the-worlds-forests/). The industry has been rife with fraud from its beginnings.

With the Blue Carbon proposals as part of California's proposed strategies for climate change, fossil-fuel companies in California also stand to make more money by supplying offsets to balance California pollution.

They also stand to need good public relations to buffer their images (https://indonesia.chevron.com/en/environment).

Chevron has already developed infrastructure in 2021 for carbon offset project development and environmental restoration, with San Jose-based Blue Planet (https://www.chevron.com/sustainability/environment; https://www.chevron.com/stories/chevron-invests-in-carbon-capture-and-utilization-startup).

Chevron is developing carbon offsets from whales and animal excrement: (https://pbs.twimg.com/media/FMPZzHIXoAMClGl.png).

They are also requesting incidental take from their drilling operations. This is one of their requests: (https://media.fisheries.noaa.gov/2021-07/Chevron_Green%20Canyon%20VSP_2021LOA_App_OPR1.pdf?null=).

The American Petroleum Institute, whose members include ExxonMobil, Chevron, and other oil companies, unexpectedly backed the federal price on carbon this past year (https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/in-shift-oil-industry-group-backs-federal-price-on-carbon-biden-deb-haaland-washington-chevron-interior-department-b1822569.html)

The fossil-fuel companies also could make more money by arguing that coastal drilling and mining on the Continental Shelf is essential, the sanctuaries not so much. Fossil-fuel money is already talking in California government and expanding its reach statewide and oceanwide.

It will be even easier to remove marine sanctuaries from some or all environmental protection if the public perception is that there is widespread toxicity/pollution/destruction already and the measure is deemed by authorities to be desperately needed—much like the current mouse population on the Farallons. If public perception trusts its authorities to do the right thing, so much the better for profiteering.

When marine environmental organizations are funded by fossil-fuel companies, it is far more likely that drilling will go unopposed and that no Indigenous archaeological sites will be found on the Continental Shelf. The fossil-fuel foxes are guarding the marine sanctuaries.

Some toxic dumps offshore in California have recently received more news coverage. There are a lot of decaying shipwrecks off the coast as well as radioactive and DDT waste. Brodifacoum will pile on more toxicity. Most people tend to look away if it's messy, and it is. The fossil-fuel industry’s offshore workers may wear hazmat suits, but they will keep working.

Chevron might take a similar approach to that permitted under the United Nation's REDD+’s corrupt offset programme, also like the doubled profit of CARB’s Mine Methane Capture Protocol—the fossil-fuel industry could initially devastate an area through resource extraction, toxicity, and environmental degradation, then get offsets and additional revenues for "capturing" methane for liquified natural gas for downstream use through other fossil-fuel companies.

Once the Blue Carbon offset protocol is implemented, the fossil-fuel companies would be compensated for improving environments they already degraded, all the while offsetting their own industrial emissions and celebrating their liberal emissions caps.

Currently, substantial underwater exploration, research, and testing on the central California Coast, also in marine sanctuaries there, is dominated and/or controlled by environmental organizations funded by Packard Foundation money, linked to Chevron. It is unlikely these environmental organizations will fight new fossil-fuel developments.

Point Blue, the organization that proposed the poison drop, wrote its own EIS, will administer the drop, and be paid by the federal government for the Farallons poison drop, has had massive funding from the Packard Foundation.

The California Coastal Commission voted 5 to 3 to approve the poison drop in December 2021. It is unlikely that they will fight the poison drop.

Island Conservation in Santa Cruz has been involved in other poison drop events and is pushing the Farallon drop. David Packard’s daughter Susan Packard Orr is on their advisory council, and grandson Heath Packard is on staff. Island Conservation has received Packard Foundation funding (https://www.islandconservation.org/advisory-council-founding-members/; https://www.islandconservation.org/dvteam/heath-packard/).

The Monterey Bay Aquarium, where Nancy Packard Burnett was a co-founder, and another of David Packard’s daughters, Julie Packard, is executive director, has its own major research efforts and has had significant Packard Foundation funding (https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/newsroom/staff-bios/julie-packard).

The Monterey Bay Research Institute, operated by the Packard Foundation, was founded with foundation funds in 1987 and does marine research (https://www.mbari.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2020_MBARI_Financials_AICPA_FINAL.pdf).

It’s not an accident that these organizations are now prominent at their diverse locations along the coast. They are extraordinarily well funded, connected, and supported. They are in position to support oil company entrees to profit from fossil-fuel extraction and carbon offset greenwashing to clean it up.

There are claims made about the Packard Foundation funding—it’s a huge fund, easily available, and given quickly. Many environmentalists, environmental organizations, and others are funded by it. This serves to convince individuals and organizations that have Packard funding to be sympathetic or at least neutral to ongoing environmental abuses by public and private monied interests if they want to stay in business.